Libya’s Migration Nexus: What It Means for UK and EU Strategy

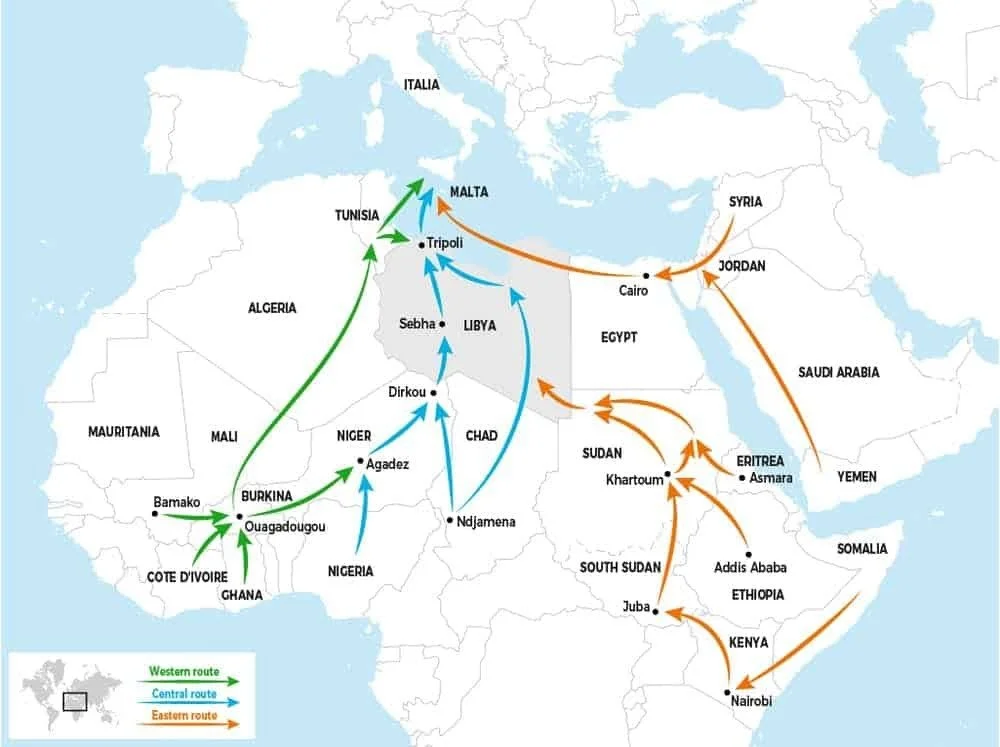

Libya remains one of the most critical hubs in the Central Mediterranean migration route, serving as both a destination and transit point for people on the move from across Africa and the Middle East. Despite fluctuating levels of European engagement, the dynamics of irregular migration through Libya are shaped by entrenched smuggling economies, shifting regional pressures, and the country’s ongoing governance fragmentation. For the UK and EU, this represents a persistent challenge: balancing deterrence and humanitarian imperatives while addressing root causes well beyond Libya’s borders.

Source: MSF

Drivers of Movement: From Sudan to the Libyan Coast

Migratory flows into Libya are fed by multiple routes, the most significant originating from Sudan, Chad, and Niger into the south-eastern Libyan town of Kufra. Ongoing conflict in Sudan has intensified this movement, with recent reporting indicating that many Sudanese refugees are now rerouting through Libya after finding conditions in neighbouring countries untenable. From Kufra, migrants typically transit to Sebha in central Libya, a key logistical hub where smuggling networks consolidate groups for onward movement north. Zawiya, west of Tripoli, remains the primary coastal departure point for sea crossings.

These movements are sustained by highly structured smuggling networks, as documented by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime and Chatham House. Networks often operate with varying degrees of complicity from local armed groups and municipal actors, embedding smuggling in Libya’s war economy. Smuggling fees can range from USD 2,000 to USD 6,000 for the full journey to Europe, with payments often staggered between each transit point.

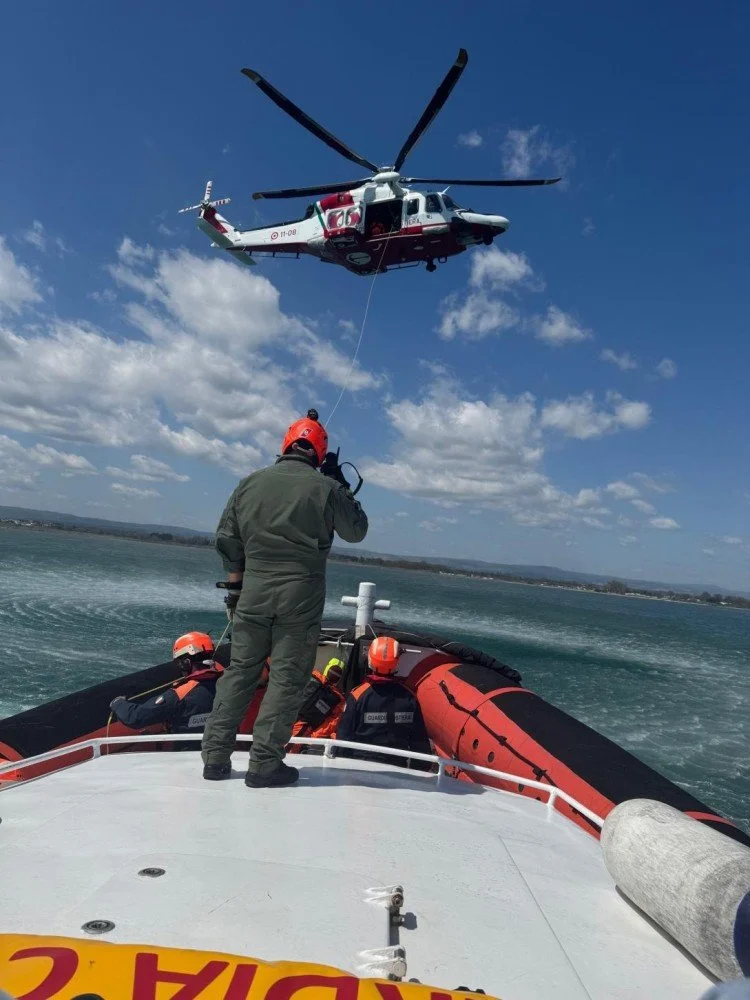

Migrants sit on a small boat, about to be picked up by the Italian coastguard.

Human Costs and the Mediterranean Data Picture

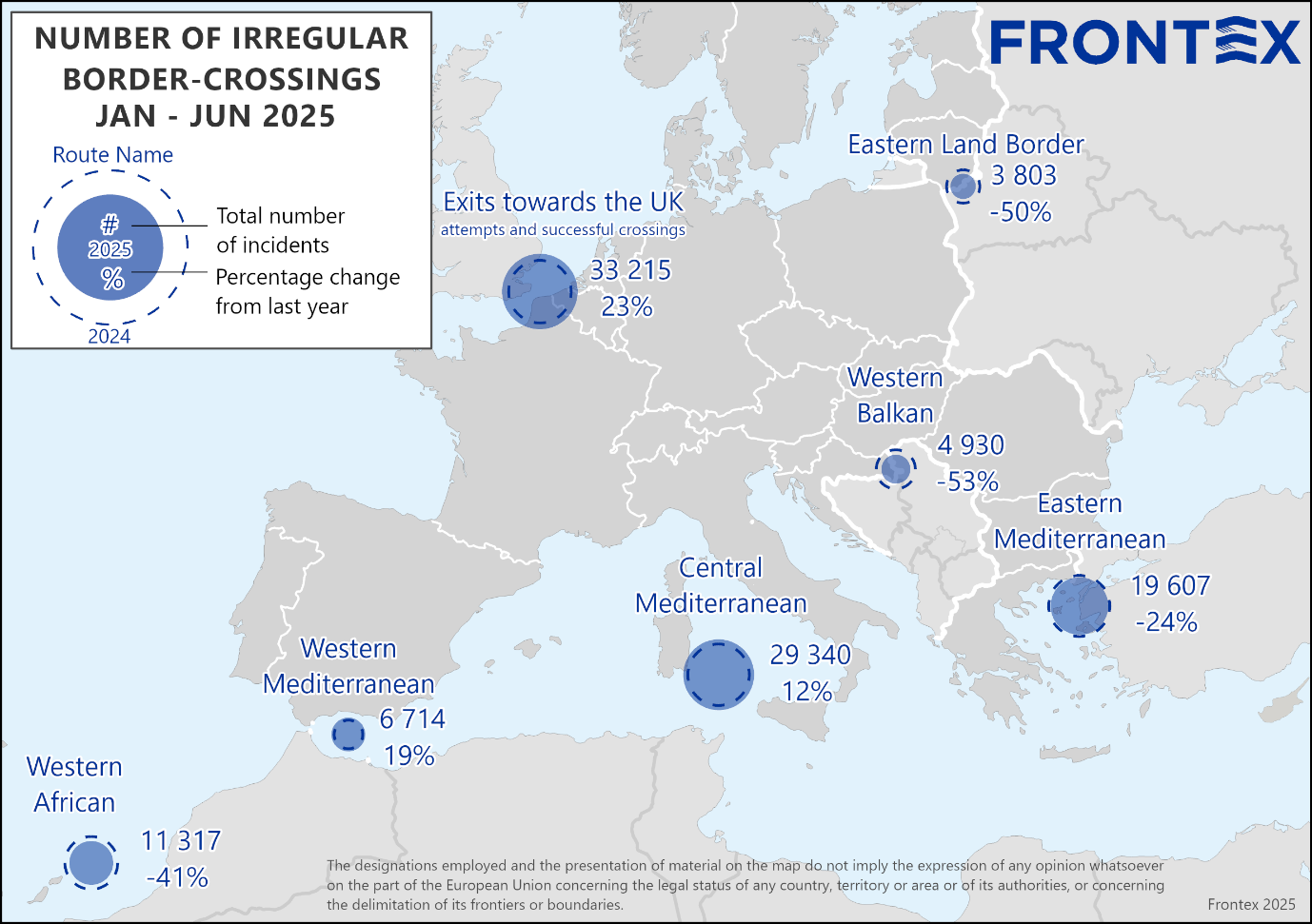

IOM data show that in Q1 2025, over 15,000 people arrived in Italy via the Central Mediterranean, with Libya remaining the main point of departure. The route is also the deadliest: the Missing Migrants Project recorded over 500 deaths in the same period, with actual figures likely higher due to unreported incidents. Conditions in smuggling hubs which often feature forced detention, extortion, and violence, compound the risks before migrants even reach the sea.

While departures fluctuate seasonally and in response to enforcement efforts, they remain resilient. Crackdowns along one section of the route often lead to displacement of smuggling activity to other areas. For example, increased Libyan Coast Guard patrols off Tripoli in late 2024 coincided with a rise in departures from more remote western beaches, beyond the reach of routine surveillance.

Source: FRONTEX

UK-EU Exposure and Policy Dilemmas

The UK and EU are exposed to this migration flow both directly, via arrivals in Italy and potential secondary movements north, and indirectly (see above), through political pressures over migration management and humanitarian responsibilities. Joint EU-Libya cooperation has historically centred on capacity-building for the Libyan Coast Guard and funding for IOM’s voluntary return programmes. However, such measures face criticism over human rights concerns, given documented abuses in detention facilities where intercepted migrants are often taken.

Libyan Coast Guard on Operations (Source: EU Border Assistance Mission in Libya)

The UK government’s approach to irregular migration has hardened in recent months, with increased collaboration with Italy and EU counterparts on intelligence-sharing and maritime surveillance, as well as reinforced sanctions targeting smuggling networks. Proposals for offshore processing remain under active discussion.

Political communication has also been explicit. In August 2025, Prime Minister Keir Starmer posted an image on Instagram showing individuals in what appeared to be a detention facility, with the caption: “I said that if you enter this country on a small boat, you will face detention and return. I meant it.” The post drew significant online criticism, with thousands of comments accusing the government of pandering to hardline positions and neglecting humanitarian considerations. Regardless of the public backlash, the post illustrates the government’s readiness to foreground enforcement imagery and messaging as part of its migration policy narrative.

Policy Implications: Stopping Migration at Source

Experience in other transit regions suggests that enforcement alone cannot dismantle entrenched smuggling economies without viable alternatives for both migrants and local communities. For Libya, this means that any durable reduction in departures will require a multi-layered approach:

Regional coordination to address flows from Sudan and the Sahel, including expanded legal pathways and protection in first countries of asylum.

Economic alternatives in smuggling hubs such as Kufra and Sebha, where the trade underpins local livelihoods.

Governance stabilisation to reduce the role of armed groups in the migration economy.

Targeted disruption of transnational smuggling finance, including cooperation with banking and remittance systems.

For the UK and EU, the policy challenge lies in integrating migration management with broader stabilisation efforts in Libya and its neighbourhood. Without addressing the upstream drivers and the local political economy of smuggling, the Central Mediterranean route will remain both a humanitarian crisis point and a source of political pressure in Europe.

Sources

Chatham House & Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Smuggling Economies in Southern Libya: Routes through Kufra, Sebha and Zawiya, 2025.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) / Mixed Migration Centre, Mixed Migration Update – North Africa Q1 2025, ReliefWeb, April 2025.

IOM Missing Migrants Project, Mediterranean Arrivals and Deaths Data, accessed August 2025.

Reuters, Sudanese Refugees Rerouting through Libya as Conflict Escalates, July 2025.

European Union External Action Service, EU–Libya Cooperation on Migration Management, 2025.

UK Home Office, Irregular Migration: Policy Statements and Enforcement Measures, 2025.

BBC News, UK Government Announces New Sanctions on People-Smuggling Networks, 17 July 2025.

House of Commons Library, Irregular Migration: Mediterranean Routes and UK Policy Responses, updated August 2025.