Syria’s Digital War: Disinformation, Sectarianism, and the Risks of R/FIMI

What's going on?

As Syria continues its political transition following the fall of Bashar al-Assad, its information environment remains highly exposed. Alongside physical threats from violent extremist organisations (VEOs) such as Islamic State, a parallel challenge is emerging in the digital domain, where foreign information manipulation and interference (sometimes referred to as R/FIMI) and coordinated disinformation efforts are increasingly shaping local perceptions, testing social cohesion, and complicating efforts to stabilise the country.

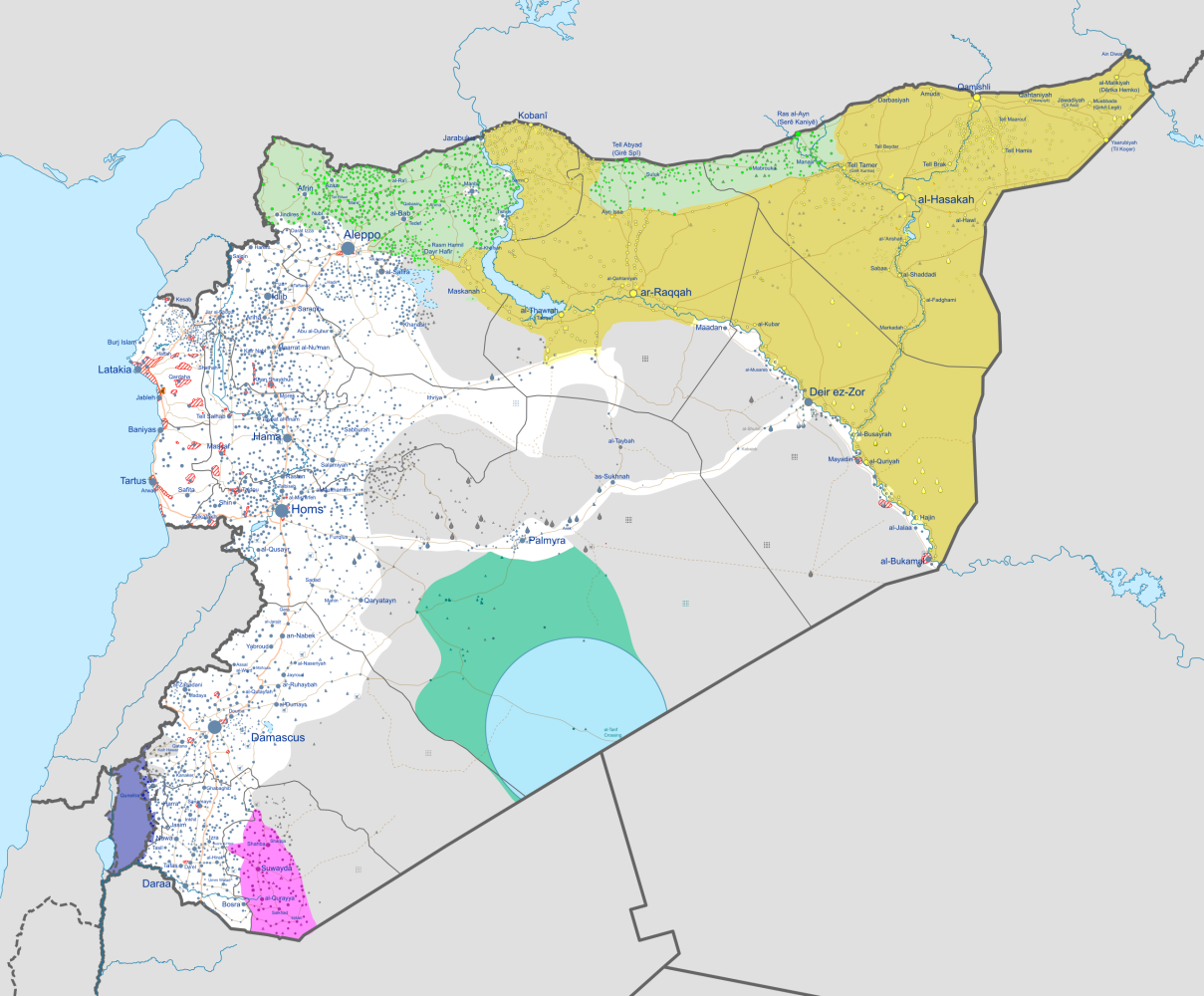

In early 2025, a series of violent incidents in Homs were followed by a sharp uptick in disinformation, particularly targeting minority communities in Latakia and Tartous. These governorates, long viewed as aligned with the previous regime and home to large Alawite populations, were the focus of an orchestrated digital campaign. This campaign leveraged AI-generated content, recycled footage from past conflicts, and spread culturally resonant narratives to amplify communal fear and erode trust in Syria’s emerging national institutions.

The clashes occurred in Western Syria, along the coast in areas closely associated with the Assad Regime.

Verify-Sy, Syria’s leading fact-checking initiative, reported that the period of April 5–7 marked one of the most significant disinformation surges since late 2024. Misleading content, which circulated largely through messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, included claims of mass violence against Alawite civilians, some of which were fabricated or misattributed. These narratives spread rapidly in the absence of trusted local reporting and in regions already concerned about potential retaliation or political marginalisation.

What distinguished this episode was its targeted use of partial truths and high-context messaging. False claims of imminent violence in the coastal governorates were introduced shortly after real attacks in Homs, increasing their plausibility. Researchers tracking the event noted the coordinated activity of Arabic-language social media accounts, some likely foreign-run, disseminating calls to mobilise and defend local communities. Nearby, tensions between Arab tribes and the Kurdish SDF in Northeast Syria have the potential to erupt, if communications were to be leveraged convincingly after a similar false flag operation.

Other strands of disinformation introduced conflicting storylines: reports of Maher al-Assad’s return with Russian support, or fabricated statements suggesting imminent international military intervention to restore Assad or establish a breakaway coastal entity. These claims, although unsubstantiated, reinforced existing anxieties and undermined confidence in the transitional government, while building on some level of truth, making the whole far more credible.

This pattern aligns with broader findings from international monitoring bodies. As the Atlantic Council has noted, Syria’s information landscape, which has so long been shaped by censorship, fragmentation, and limited access to reliable news, remains highly susceptible to manipulation. It may be that because levels of trust are so low, and some sources so biased, that anything resembling an independent media is almost impossible in the near-term future. In areas like Latakia and Tartous, where media penetration is low and concerns about collective retribution remain, unverified content often circulates unchecked.

While some of the more prominent falsehoods were later disproven, including through video testimonies from individuals erroneously reported dead, the narratives had already shaped public sentiment. Local groups organised informal security patrols and support for armed non-state actors increased, not necessarily out of ideological alignment, but as a reaction to perceived threats.

Policy Implications: Addressing Online Harms in Post-Conflict Transitions

The April 2025 incidents highlight the importance of integrating information security into post-conflict stabilisation strategies. Disinformation, particularly in environments marked by insecurity and low institutional trust, can quickly influence behaviour and disrupt fragile political processes.

Key areas for intervention include:

Early warning and monitoring systems, including CSO groups and local actors, capable of detecting and analysing harmful online narratives with potential to incite real-world harm;

Strengthening independent verification initiatives, or institutions, to enable timely responses to circulating falsehoods;

Investing in digital literacy and trusted communication channels, particularly in underserved regions where rumour often outpaces formal information, or areas where digital literacy is lacking, including rural areas;

Building resilience against R/FIMI by identifying and disrupting foreign-linked influence operations that seek to exploit sectarian or ethnic fault lines.

The interim government’s recent step to launch a national news outlet is a useful first move. However, without a broader ecosystem of credible, community-level communications and digital safeguards, such initiatives will struggle to outpace increasingly agile disinformation networks.